(This article was originally published in the GB Newsletter. Be sure to sign up for the Newsletter by clicking here.)

How many times have you heard the words “holistic”, “sustainable”, “empowerment”, and “grass-roots development”? All great terms, but what is their significance? How often do you sit and think about what it means to make it possible? Well I have good news and bad news. The bad news is that there isn’t a step-by-step guide for implementing sustainable development projects. The good news is that every brigader, staff member, donor, community member, supporter and critic has been fulfilling their crucial role in finding the answer by questioning, discussing, providing feedback and then implementing changes so that we can realize our mission of sustainability and holistic development. Some of the more recent initiatives include the advancement of our Community Health Workers program, the Referral Program, new Medical Brigades model and the Community Research and Evaluation team. Today, however, we will be discussing the exciting changes occurring in Panama. Up until this point, we have worked in various regions across the country with several partner organizations. The partner organizations provided us with communities and projects, and we organized two to three brigades to each community, during which we worked alongside the partner organization. This model was extremely effective, especially for the beginnings of our programs in Panama, because these organizations not only had the trust of the community, but were knowledgeable of the community’s background and needs. Additionally, they had continuous contact with the community and were capable of preparation and follow-up in conjunction with the Panama team.

Brigades were successful and the communities and partners were pleased with the work, however, working in various regions with different partner organizations across the country of Panama posed many challenges for our Panama team members. Most importantly, the Panama programs were unable to work together to establish holistic models in the communities they served, since partner organizations worked in different communities and usually only worked with one or two program leads. Additionally, it added logistical barriers for our Panama team members to provide as much attention as they desired in each of the communities we served. Aside from programming, planning 20-30 brigades a season across the country was very difficult for the logistics team and increased the cost of running brigades. These factors would make it simply impossible to continue at our rates of growth. With some brigades, for example, a higher percentage of program contributions would have to cover transportation and lodging, which would then take away from programming. For this reason, we decided to choose one region of Panama with the most “in-need” communities that were also logistically feasible to access. From there, we will establish a central location for students and staff to stay and implement a “community immersion model” in all of the surrounding communities in the area. In this model, all of the Panama programs (Business, Dental, Environmental, Law, Medical) will work together holistically to address the central health and development needs in each community.

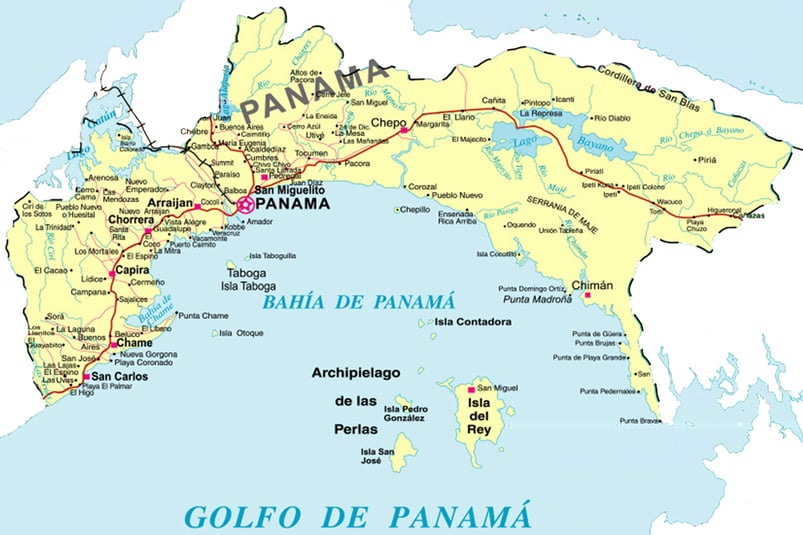

To achieve this transformation, we developed a plan of action in order to determine the correct region for the future of the organization. The team first started by collecting all available census and ministry data and analyzed the key health, socioeconomic, educational, legal and environmental indicators to discover the most under-resourced regions. The data proved that the indigenous Kuna, Embera and Ngobe communities had the lowest access to basic resources and had little support from other NGOs and government organizations. The majority of these groups are located in the regions of Kuna Yala, Ngobe Bugle, around the Panama Canal, Eastern Panama and Darien. The next step was to research these regions in more depth and gather anecdotal information from NGOs and government organizations that had experience in these areas. Fortunately, we had implemented projects in all of the aforementioned regions; therefore, staff could also provide very valuable feedback. Throughout these meetings, we considered important factors such as safety, road access, distance from capital city and history of volunteer work in the area to ensure that our team could run brigades with university students year-round. Each meeting was instrumental in the decision making process and each meeting uncovered vital information that cannot be found in data and statistics. One organization with experience in Eastern Panama informed us of the region’s high population of Kuna, Embera and campesino communities without access to basic health and economic resources. Additionally, they mentioned the lack of NGO and government support. At this point, we had ruled out the Ngobe Bugle region due to difficult access and also ruled out the area around the Panama Canal due to high NGO presence and low density of the population. The two regions that remained were East Panama and Kuna Yala.

We were getting closer to finding the right region for future operations and now it was time to meet with local organizations and the community leaders. The Community Research and Evaluation team in Panama, which includes a past Peace Corps regional coordinator in the area, first set up meetings with the one Savings and Loan Cooperative in Torti, the Ministry of Health in Chepo and the Congreso de Kuna. Their knowledge of the region and past experiences with the communities helped the team understand the needs in the area and the potential of us working with the communities. They also provided invaluable guidance in developing a strategy for community visits. Within three weeks, the team visited 12 communities, completed 7 initial assessments and formed strong connections with many other NGOs in the area. After many meetings and discussions, the decision was clear and, at the end of March, the team officially decided to move forward with choosing East Panama as the future region for our operations in Panama. An exciting benefit is that we will also have the opportunity to continue working with the indigenous Kuna communities in Kuna Yala as they are located north of the Eastern Panama region.

Specifically, our team will be working in communities east and north of Canitas (point on the map) and communities around Lago Bayano. Through the initial community assessments, the Community Research and Evaluation has found that on average each community has limited access to healthcare and public health education, is plagued by mismanagement of waste and deforestation and has little to no access to microfinance, business consulting and legal counsel. We are confident that through our health and development programs, we have the ability to make a lasting impact in the lives of these communities and it’s our student leaders who can make this happen. The first pilot brigades will take place in May and our team will be working in the communities of Piriati Embera and Torti Abajo. For more information on the communities, please go to this link. Please stay tuned for more information about the region, brigades and communities. Consider this a call to action for all of our students to lead a brigade to Panama and help us transform this region. We are looking for dedicated and passionate student leaders to drive this initiative!

Sincerely,

Gabriela Valencia, Executive Director of Global Brigades Panama and the Global Brigades Panama team.

Business Brigades volunteers work with community bank loan officers to consult potential borrowers on improving financial sustainability. The business brigade volunteers serve as a catalyst to loan borrowers, providing consulting methodologies, financial workshops and donating a “capital investment” to the community bank to back the loan.

Environmental Brigades volunteers work with families and community leaders in rural villages on improving environmental sustainability. Volunteers develop strategies to address the socio-economic challenges that link to resource depletion and by providing education to community members on the importance of preservation while expanding their farms or businesses. Volunteers’ activities are focused on reforestation and waste management.

Law Brigades volunteers work with Panamanian lawyers to provide pro-bono legal consulting. Volunteers provide services to remote communities using a free legal clinic model, where volunteers shadow and assist lawyers as they provide legal consulting to community members. Additionally, volunteers work to incorporate unregistered communities to empower them with rights and government benefits that they would not have received otherwise.

Medical Brigades volunteers have the opportunity to shadow licensed doctors in medical consultations and assist in a pharmacy. Each partner community receives a brigade every 3 to 4 months where hundreds of patients are treated and volunteers deliver public health workshops.

Dental Brigades volunteers have the opportunity to shadow licensed dentists in urgent and preventive dental services in communities with limited access to healthcare. In conjunction with our program, Medical Brigades, each of our community partners receives a brigade every 3 to 4 months where hundreds of patients are treated with fillings, cleanings and extractions, and are given dental hygiene workshops.